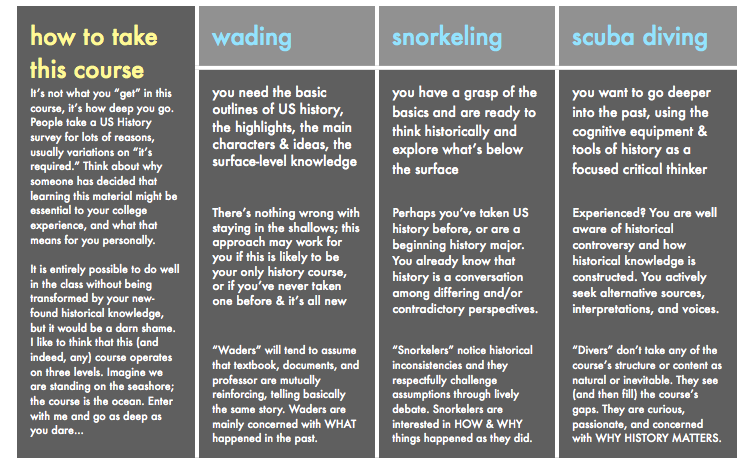

Last week, while searching for “creative syllabus” examples, I found Tona Hangen’s syllabus for U.S. History from 2011. Today I finally read through it. and was intrigued by her advice on how to take the course:

Admittedly, when I first glanced over the syllabus, I skimmed past this section because the wading/snorkeling/scuba diving metaphor seemed cheesy. But, after reading through her descriptions of the different levels of deepness, I like the comparison. I especially like how she links the different levels of deepness with questions–what, how and why–and offers a guide, not a strict or too-specific set of rules on how to take the class. And I like how she invites her students to reflect on why they are taking the course. She writes:

Think about why someone has decided that learning this material might be essential to your college experience, and what that means for you personally.

Tona Hangen

She invites her students to “enter with me and go as deep as you dare.” I wonder, how does she evaluate these different levels of deepness? Can you get an A if you only wade? I always disliked grading students. I can imagine students freaking out about how deep they needed to go in order to get an A.

I don’t want to borrow her model here, but it is inspiring me to think through what my model is. I’m thinking about my ideas of ruminating like a cow and reading like an owl eats:

But here I would ask for your patience since it turns out that critique is a practice that requires a certain amount of patience in the same way that reading, according to Nietzsche, required that we act a bit more like cows than humans and learn the art of slow rumination (307).

Judith Butler

Eat like an owl: take in everything and trust your innards to digest what’s useful and discard what’s not.

Peter Elbow

Final note: I found the syllabus for Hangen’s most recent version of this class. Her three levels of deepness aren’t on it. Why not? Did they fail to work? Did they not fit with Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs) or the guidelines for her department?