Note: This is the fourth processing blog post for my new book project. I’ve decided to do daily posts on all of my ideas instead of separate posts on each thought. Still not sure if this is the best approach.

On Not Being an Expert

Lately, I’ve developed the habit of listening to podcasts while I run. This morning I listened to an interview with Miranda July on Michael Ian Black’s totally awesome podcast, How to be Amazing. In the opening soundbite, July says:

Being a beginner, again and again, that’s a good feeling to me….And the feeling of being a pro and a master of this particular thing, that whole thing sounds nice, like I’d love the respect part of it, but it doesn’t sound fun creatively.

Miranda July

This idea of not wanting to be a Pro resonates for me. I always like experimenting with new methods and ideas. It helps keep me curious and excited. When I was a teacher, many of the readings I assigned were new to me. I liked discovering them with my students. Now, as a storyteller who experiments with a lot of online tools, I’m always trying to craft and tell stories in new ways. Once I’ve used some tool for too long, the creative process isn’t as enjoyable.

My resistance to being a pro (or expert) is about more than losing my creative flow, however. As an ex-academic, and a child of an academic, I’ve witnessed firsthand the effects of too much expertise. People often become arrogant assholes. I’ve written a lot about not liking experts/pros, including this mini-essay for my first book and these haikus:

The shift from student

to expert is the end of

new ways of thinking

I don’t like experts,

They claim, “I have THE answer!”

when I want questions.

I dropped out when the

demand to be an expert

was forced upon me.

Watch out for people

who claim to be experts.

They are often jerks.

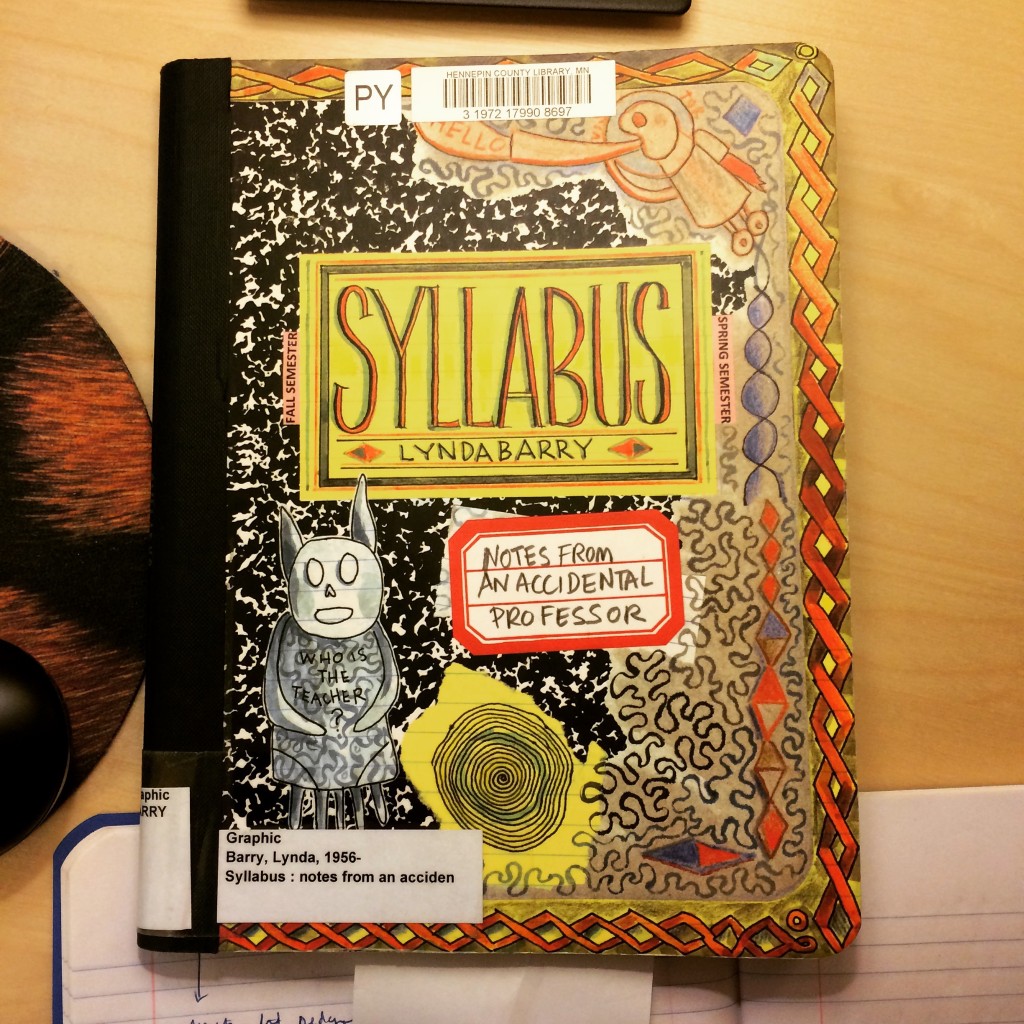

Why am I writing about this in my processing blog post? I envision this book project to be partly (mostly?) about my pedagogy and my work/stories as a teacher/guide/role model. I don’t want this book to be a how-to guide or the pontifications of an Expert. How can I do that? As I write these lines I’m questioning myself and my dislike of expertise. What’s wrong with acquiring skills and being proud of your knowledge? How is my creative/critical work harmed when I always only want to be a beginner/non-expert?