Here is (hopefully) the final installment in my analysis of Welcome to Pine Point. (pt 1, pt 2a, pt 2b)

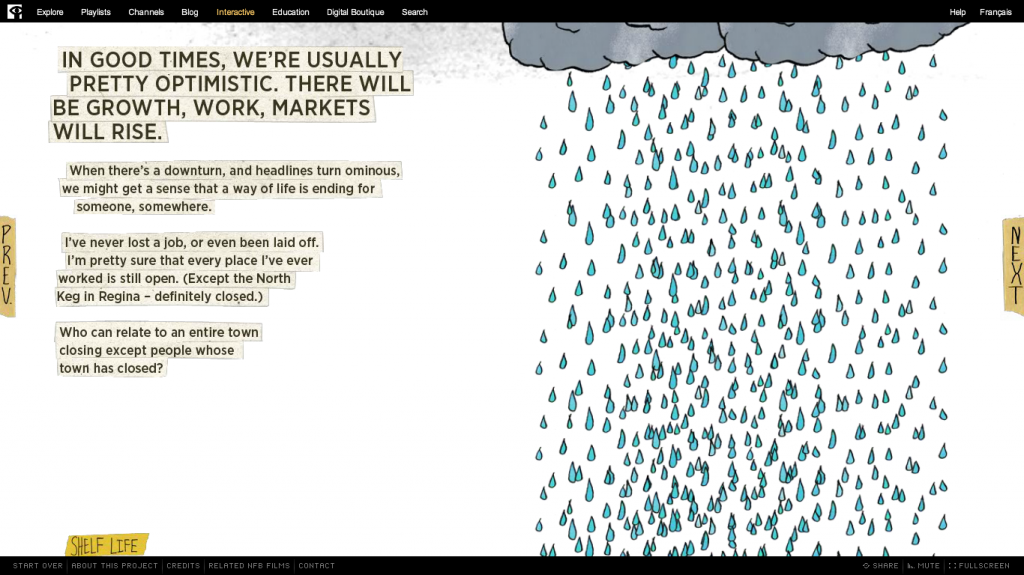

chapter five: Shelf Life

On the opening page of this chapter, the text reads:

I’m bothered by the last line:

Who can relate to an entire town closing except people whose town has closed?

What does the narrator mean by this question? And what is its intent? While I’d like to read it as an introduction to the next two pages in the chapter, when two Pine Pointers discuss leaving Pine Point, that’s not the immediate effect. I read the question as another example of the narrator positioning people in Pine Point as exotic others that we (the users) can gaze upon and learn about. We, because we can’t relate to them (but who says everyone who might read/view that “we” can’t relate?), are different from people in Pine Point. Not sure if this makes sense?

chapter six: What’s Weird

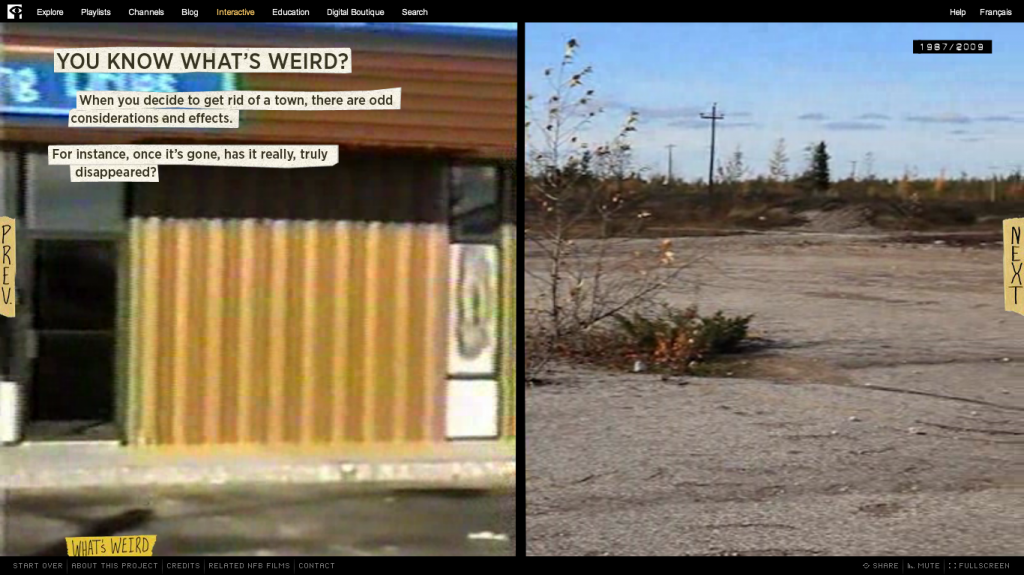

On the opening page of this chapter, there is an unidentified (and disembodied) voice discussing how it’s weird to think about Pine Point not existing anymore. On the page is a split screen with two sets of footage: on the left is Pine Point 1987, with various buildings, on the right is Pine Point 2009, with barren fields. It’s a powerful page, made even more powerful by the haunting music in the background.

chapter seven: Remains

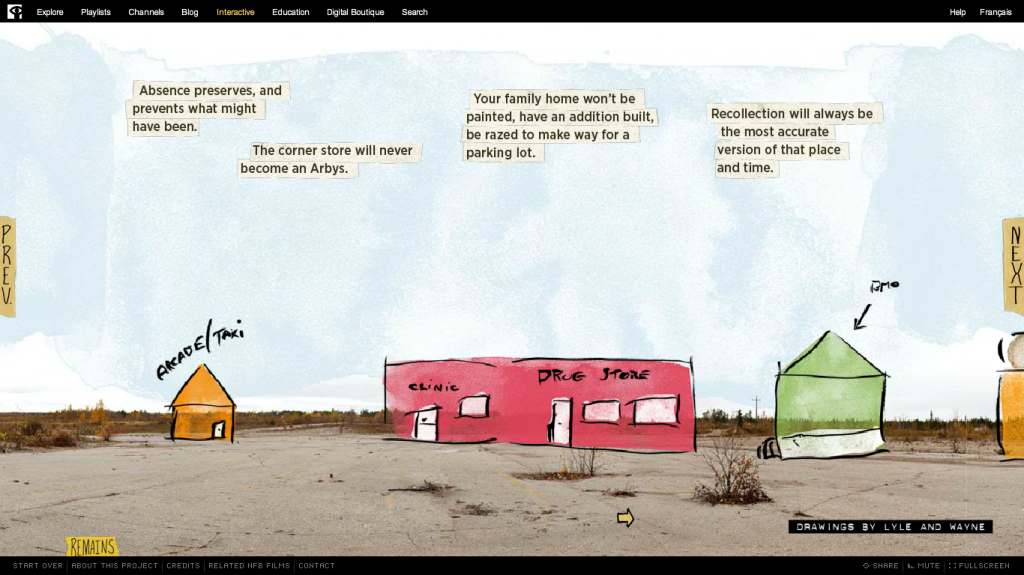

This chapter discusses how losing the town meant it never changes—it can’t, it’s gone. This allows Pine Pointers to not just remember it, but memorialize it as a wonderful place, where nothing bad happened.

This text seems to be the answer to the question that open the entire documentary:

This chapter also introduces the “big surprise”/twist of the story (which I won’t reveal here).

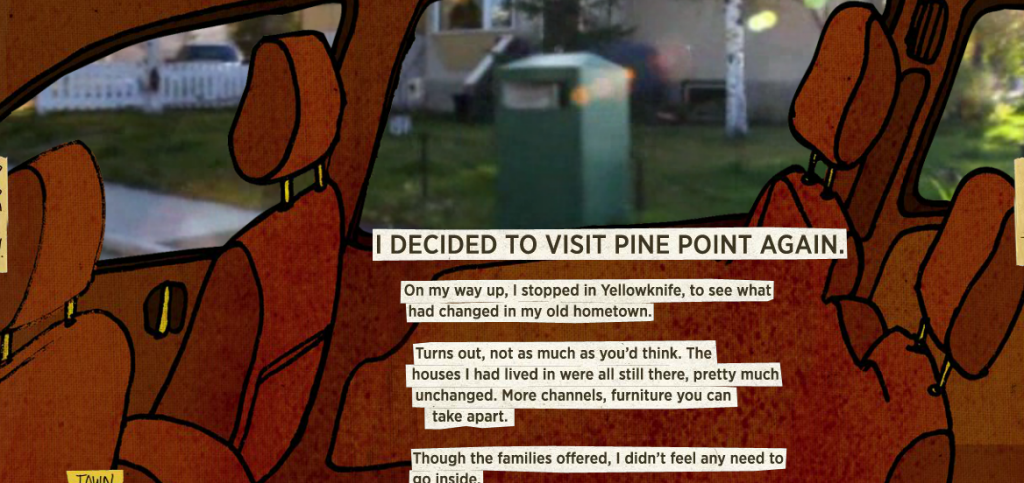

chapter eight: One for the Road

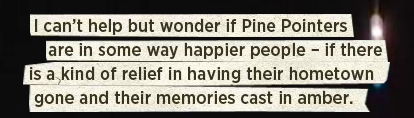

On the final page of the interactive documentary, the narrator wonders:

This passage fits the overall tone/mood of this interactive documentary. Again, it positions the narrator (and us, I think?) as forever distanced from the Pine Pointers. We will never know how they feel/what they felt—we can’t understand—because their experiences are too different from ours. What would this story look like if he had asked Pine Pointers if they were happier? If there were (more) accounts (or, because it’s an interactive documentary, opportunities for them to share their stories online) of their responses to this question.

I deeply enjoyed this interactive documentary and count it as one of my big inspirations, so my critical questions aren’t meant to devalue or dismiss it. I think my persistent questions about the narrator and how they position themselves (and us) as distanced from the subjects of the story come out of my own struggles to figure out how I want to position myself as a narrator in the farm project.

More on that later…