some preliminary thoughts…I must admit that I’ve been working on this post for a few days and I’ve struggled to express myself. Too much resistance, but to what? Ugh! Although this is not quite finished, I needed to post it here. I’m hoping to build on it and eventually use (at least) some of it in my book project.

I’m in the midst of archiving all my past assignments for my book project. After feeling stuck for several days on my teaching philosophy statement, I decided to change how I was working. Instead of continuing to write page after page of notes in my green notebook, why not find all of my old assignments and review them to see how I actually taught and not how I thought I taught? This was a smart move. It’s illuminating to look back on the assignments that I chose and how I organized them.

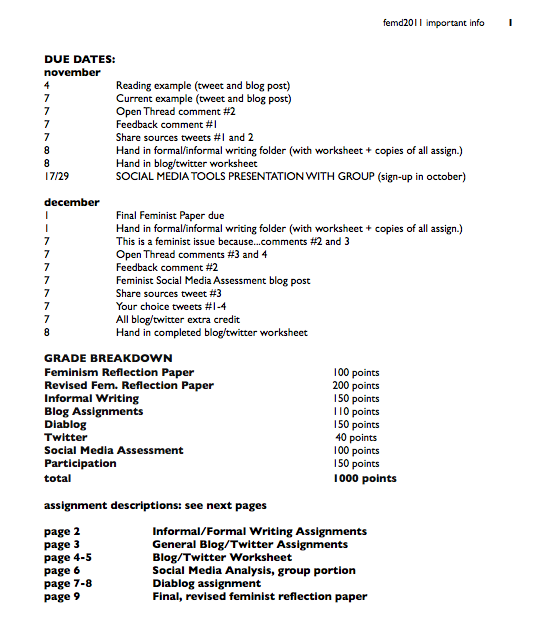

My first reaction: Wow. I have a lot of details in these assignments! It’s a bit out of control. For example, I created a pdf of all of the course assignments for my Feminist Debates (fall 2011) course that is 9 pages long. 9 pages of detailed directions.

Why did I do this to my students?

Pondering that question for a moment, I remembered one of the earliest feminist pedagogical principles that I adopted as a women’s studies grad student, teaching one of my first courses. In a feminist classroom, students encounter new ideas that challenge their ways of knowing. And they are encouraged to not passively receive the answer from the Teacher, but actively explore how and why knowledge is produced. This is unsettling and troubling, even as it is often exciting and transformative. Students can benefit from structure to direct these new ways of learning, thinking and teaching.

Without structure, students can become overwhelmed and lose their way. So can teachers. Left unchecked, without some sort of structure to guide me or rein me in, my thinking and teaching becomes too much…for students, friends, family members and, at a certain point, me.

In reviewing old teaching materials, from syllabi to class summaries to in-class assignments to big class projects, I see structure everywhere. A highly ordered syllabus. Class summaries that are broken up into very specific parts, to be completed within exact amounts of class time…10 minutes for announcements, 20 minutes for an introduction to the topic, 20 minutes for small group, etc. And detailed assignments that encourage students to find their own ways to challenge and connect with class concepts, but that ground those challenges and connections in focused (and directed) methods.

Ah yes, the assignments. A primary way in which I imposed structure within the classroom was through highly choreographed assignments. And the primary way in which I communicated and managed that structure was through my detailed directions for those assignments.

Lots of Directions.

While I was always reluctant to introduce a lot of specific classroom rules (I despise disciplining students or fostering spaces marked by what you can’t/shouldn’t do), I never shied away from detailed directions on assignments. Why?

- To anticipate and preemptively answer basic questions about the assignment (when it’s due, does it need to be typed, etc).

- To manage/direct flow of engagement, especially online.

- To break up intimidating/difficult/overwhelming assignments into manageable parts for students and the Teacher.

- Because it feeds my love for elaborate planning–the more thinking through that it requires, the better! Is that bad?

As my teaching became more experimental and involved efforts to challenge/resist/transgress academics-as-usual through the blending of online and offline spaces, my directions became more detailed. I made them more detailed partly because using blogs and twitter effectively requires a lot of thought and deliberate action–without guidance, students often won’t post much or will post a lot but all at once or will frequently post uncritical, superficial junk. And I made them detailed because I needed some ways to manage and mitigate (?) the resistance that some (not all) students (consciously and unconsciously) were expressing to these experiments. Resistance to new ways of engaging. Resistance to the extra work and learning that these new ways demanded. What does that mean? I need to think through it some more.

I have much more to say about directions, but I’m tired of writing this post now. So, I’ll end with a few questions to ponder:

- How much detail in directions is too much?

- What are some other strategies for helping students as they engage with difficult and uncomfortable ideas and practices?

- As I became more invested in a feminist/queer pedagogy and critical of the academic industrial complex, my teaching practices become more experimental. How much experimenting is too much? When is it irresponsible to the students and their well-being?